|

«That's it!» |

An old craft made for eternity.

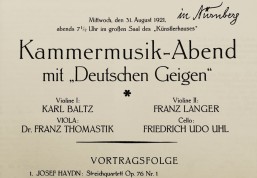

Building violins, violas and cellos doesn't take place in quiet environments. Even though the renowned German string instrument builder Wolfram Neureither spends about half of his time working in his workshop in Montpellier, Southern France, the exchange with his colleagues and plenty of international travels, delivering and repairing instruments, or visiting fairs and exhibitions take up significant parts of his time. Born in 1967 in Eberbach, Germany, Neureither learnt his craft in 1990-93 at the violin making school in Newark-on-Trent in the UK, which back then was known as a young and innovative school. There he learnt to work free from traditional boundaries, and with enthusiasm and love for detail.

Wolfram Neureither

Neureither originally moved to Montpellier, when he was offered an assistantship by violin maker Frédéric Chaudière in Montpellier, upon his graduation. In the 80s there used to be three workshops remaining in the city, two of them in the tradition of Cremona's violin maker school, and one in the tradition of Newark-on-Trent. Following the continuously raising numbers of co-workes who became self employed, the number of workshops has increased to meanwhile 14, giving this city by the Mediterranean Sea the status of a violin maker metropolis.

In 2000, Neureither opened his own workshop. Almost a third of his creations are violas. Violins and cellos make for the remaining two thirds. At the competition of Pisogne in Italy, he as honored for one of violas, receiving a special price for the best sounding instrument. What he likes about the viola specifically, that's the freedom and possibilities for variation. He occasionally uses simple wood pieces acquired straight from the forester, achieving remarkable results. Among his many enthusiastic viola clients are Michael Klotz, Noemie Funez-Palencia, Anne-Sophie van Riel and Martin Hahn.

He is a frequent guest at exhibitions in Europe, the USA and in the Far East, works as a co-organizer of his own events, academies and festivals in Montpellier. He teaches violin students at an international workshop in Izmir, Turkey. As a violinist he plays in different ensembles himself. The creator of string instruments receives a lot of critical appraisal from around the world. There's one situation he recalls with particular pride: When a friendly violin dealer from New York tried one of his instruments, he couldn't hold his excitement: «That's it!».

Montpellier, France

Mr. Neureither, Montpellier is one of the leading centers for violin making, next to Cremona. Why is it that so many world renowned violin makers have gathered here?

Montpellier is a beautiful city with lots of daylight and a mild climate. There's an active music scene with an «Orchestre National», a large music school and the «Festival Radio France-Montpellier» during the weeks of July. The city is home to the «Opera Comedie», a wonderful theatre in Italian style, and with the «Corum» of one of the biggest and most modern, national concert venues. Paris and the rest of the world can easily be reached from here, thanks to the TGV and the airport. That is very important, since a violin maker depends on an international market when creating new violins. The 12 to 14 workshops in this city all specialize in creating exclusively, or at least mostly new violins, violas and celli. And the majority of assistants who once found employment, are becoming self employed here, just like me back in time.

What are the origins of violin making in Montpellier?

Montpellier is known for having Europe's oldest medicine school, and for its university. Even though there have occasionally been violin makers in the city over the past centuries, a musical «tradition» only started in the 70s, with the founding of the Orchestre de Montpellier; and a violin maker tradition started in the early 80s when three violin makers moved here, two being graduates of the Cremona violin maker school, and one being a graduate of the Newark-on-Trent violin maker school.

What is the added value for you personally, in having renowned colleagues as neighbours?

The exchange with many of my friends is very nice, intense and friendly. It prevents detours and saves time, for example in regards to good lacquer recipes, best sources for wood, or the rediscovery of lost techniques. Thanks to this dynamic collaboration, were have been able to organize a few large and ambitioned projects in the past: the big Stradivarius exhibition in 2008 with over 20 instruments of the master and a performance of a complete Stradivari orchestra, the violin maker festival of 2011, and a long lasting series of masterclasses with internationally renowned soloists and talented students.

How do you respond to the cliche of violin making being a dusty, old fashioned craft?

I agree that violin making is a very old fashioned craft - and I am very proud of it! In this case, it seems to prove that the violin is one of the most successful and perfect inventions of history - and impossible to improve on!

Do you build the whole range of string instruments?

All except for the string bass.

Which instruments are you best at making?

My biggest affinity is with the violin, which I play myself. I love the imposing dimensions of the cello, which make for a refreshing change, and are even somewhat closer to cabinet making.

With the viola, I like the freedom and possibilities for variation regarding the instrument size, the choice of wood, the height and form of the curvature, the fineness or rather rusticity of the work - with the viola, all of these choices can be successful.

Would you call the everyday work of an instrument builder the work of a lonely inventor, who spends weeks and months in isolation, working on his instrument?

Violin maker is one of very few professions nowadays, where the complete work process lies in just one hand: from wood cutting up to the delivery of the finished instrument and the calibration together with the client. There isn't a lot of time to fiddle around in solitude. On the contrary, I think that seeing and perceiving the world around you is a guarantor of success when creating an instrument of good quality.

How much of your time working, talking in percent, do you spend on the instrument in your workshop?

I spend about 50 percent of my time working on the instrument and in the workshop. Then there's a few percent for paperwork, phone calls or emails, and then there's a big part allocated to traveling and delivering instruments, maintain them, or participating at fairs or exhibitions. I travel to Taiwan, China or Japan or Germany, and to various European countries on multiple occasions per year.

How much time does it take to create a good instrument?

Looking at a later violin of Guarneri del Gesu, one may conclude that building a very, very good violin can be a very quick process - provided that the violin maker is experienced, has a good concept and best materials available.

What are the costs of an instrument?

The costs of an instrument primarily depend on the amount of working hours and the violin makers reputation. The material costs hardly ever exceed 10% of the sales price.

How far can you customize the instrument's sound or design to meet a musician's wishes?

That is very difficult. With year of experience, I think one develops some experience in regards to interaction of wood, model, curvature types, plate strength and so on. And even though one can be wrong at times, there's the fact that the finished instrument can still be thoroughly customized, for example with the placement and length of the soundpost, the height and form of the bridge, the choice of strings,...

How much better does a good musician play on a customized instrument, compared to a more «generic» one?

A good musician should be able to play well on almost any instrument. This is the responsibility of the violin maker, particularly the «generic» aspect should be maintained, at least with violin or cello makers, in regards to string length, string height, etc... The fulfillment of a musician's special wishes is often difficult for us violin makers, since these wishes often relate to fractures of millimeters, or very subtle changes to the form. At the same time it is these tiny details telling us about the playing style, philosophy or even psychology of a musician. I also often enjoy working for musicians, who are somewhat open to approach an uncustomized instrument. However, this openness is naturally bigger with - sadly - Italian instruments of considerable value, built in the 18th century, than with newly created instruments.

Where do you order your parts from?

A great side effect of the «violin maker centre» Montpellier is the fact that wood dealers from Eastern Europe have come by hear for many years. Very nice pieces (maple) are being delivered right to your door. A few years ago I bought maple in my village in the Odenwald. This works really well for violas, and is aesthetically satisfying. I build many celli with poplar, and there are some clients who prefer maple celli. I order all spruce pieces for ceilings from wood dealers in the Alpine region, South-Tirol and Northern Italy.

How much influence do the materials have on the sound?

The wood is obviously of utmost importance for the sound, whereas, just as mentioned before, good sounding wood doesn't always need to be deeply flamed maple. The age is surely relevant, however in my opinion the growth, density and time of the tree cutting are more important. If you have the choice between an old, but heavy piece of spruce, or a relatively fresh, but light one, your choice should be the latter.

How many violas have you created in you career?

I haven't counted them, but it must be around the 50 violas.

Who are your most famous, successful and grateful viola clients?

Michael Klotz of the Amernet Quartet plays one of my violas. Recently there've been

Anne-Sophie van Riel, who studies in Freiburg and is on her way to a great career, or Noemi Funez, a very talented violist from Madrid, who has been studying at the Conservatory Reina Sophia for a year. By the way, the gratefulness very much comes from my side. I am sure that both will advance to very deserving representatives of a new generation of musicians.

Have there been any regulars, who have ordered different instruments from you?

In most cases, people buy one instrument. There's a collector in Shanghai, who owns multiple of my instruments: Violins, a viola and a cello. There's also teachers who pass on to students and reorder. I have never built Baroque instruments, however I am considering it for the future. A few of my

clients play modern and Baroque, and there've been occasionaly inquiries.

Tell us about your most challenging professional situation.

A few years ago, a very, very good, young violinist played my violin for the encore of her concert. Immediately after the performance, she wanted to buy the instrument, however I had already sold it to somebody else on that morning. A few weeks later she sent me another email, asking if the "wonder violin" still existed...

What is your current work in progress?

I am currently lacquering a cello.

Wolfram Neureither, thank you very much for sharing with us this exciting insight on the profession of a string instrument maker.

Niklaus Rüegg

This blog article is written by Niklaus Rüegg, graduate of the Zurich International Opera Studio, graduate of the Basel Opera Academy, twice winner of the Migros Gifted Scholarship, numerous engagements in opera, operetta, musicals and concerts in Switzerland and abroad.

Rüegg has also been working as a music journalist for ten years and is responsible for the association pages of the VMS (Verband Musikschulen Schweiz) in the Schweizer Musikzeitung. As a young man, Niklaus Rüegg had played the violin and viola.

Photos: Wolfram Neureither, 2018

|

Write an input |

2. Find the composer or work for which you want to write an input.

3. On the right side: click on «Write an input».

Pseudonym

Your input will only be published under your pseudonym. Under «My account» you can enter your pseudonym at any time.

| Telemann in our online shop |

| You may also be interested in |

I am in the process of restringing my Ritter viola with Belcanto strings by Thomastik-Infeld. Part of me loves the process, part of me despises it. I am happy for these are the only strings that fulfill my needs on this specific instrument. And I am unhappy about…

» To the viola blog

Keeper of a Viola Treasure

The literature described in his epochal viola guide «Music for Viola» has all been played, described on index cards and archived by Konrad Ewald himself. Most of it is, or was, in his possession and is neatly arranged and filed.

» To the viola blog

Research Topic Viola Music

The musicologist Phillip Schmidt has dedicated himself to 18th century viola music. Schmidt originally wanted to become a singer or chemist, but then decided to pursue a career in musicology. He pays special attention to the viola, his favourite instrument, which he also plays himself.

» To the viola blog

Viola letter |

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our viola letter will keep you informed.

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our viola letter will keep you informed.» Subscribe to our viola letter for free

|

|

Visit and like us on Facebook.

Visit and like us on Facebook.» Music4Viola on Facebook