Research topic Viola music |

Musicologist Phillip Schmidt has dedicated his career to the viola music of the 18th century.

in Halle an der Saale

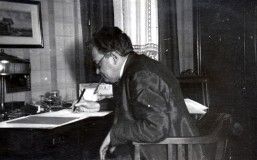

Niklaus Rüegg - A remarkable number of text inputs on music4viola have been contributed by Phillip Schmidt, a musicologist living and working in Leipzig. Schmidt was born in 1986 in Bad Saarow (eastern Brandenburg) and went to school in the closeby little town Fürstenwalde, graduating high school in 2005. He studied music science from 2006 to 2012, enrolling as a master student in 2009, focussing on «research of old music» at the Technische Universität Dresden. His master thesis discusses the string quartets of Weimarer court music director Ernst Wilhelm Wolf (1735 - 1792).

Schmidt originally wanted to become a singer or chemist, however he decided to pursue a career in musicology. His scientific focus lies in the 18th century, with particular attention on the viola, his favorite instrument, which he plays himself too.

You originally wanted to become a singer. Do you have any regrets about your career choices?

Not at all. I am happy with my career the way it worked out.

What are the prerequisites for becoming a musicologist?

It is a good starting point to have some education in music, be able to play or have mastered an instrument. Apart from that, the common requirements for human sciences apply. I had to absolve an entrance exam: An instrumental and vocal performance, ear training and rhythm exams, as well as a stylistic analysis of one music piece, out of a selection. The coursework does not expand on practical musical skills. Theory, on the other side, is the centerpiece: Texts, sources, composition styles, music history, music theory, music aesthetics.

How many unexplored areas are left in music history, as of today? Have most of them been researched?

As a matter of fact, no: There are many specialized fields, which are still shaped by musicology views of the 19th century, and have only been researched on the surface. The goal is to reappraise these fields, one after an other, to gain a more holistic, respectively differentiated insight. Musicology used to be very judgemental, focusing on just a few composers, such as Bach, Händel and Mozart. Today's view is broader, and efforts are made to establish a neutral perspective, giving much more consideration to other relevant aspects.

As a student you had already worked with the publisher Ortus-Verlag and contributed to the Halle Händel Edition. Where do you currently work?

I am employed with the Institute for Music at the Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, however my workplace is at the Händel-Haus. That's where I work part time (60%) on the Halle Händel Edition. As a scientific institution, we collaborate with Bärenreiter Verlag Kassel, who publishes the Hallische Händel-Ausgabe.

What does your typical day at work look like?

We study manuscript drafts, consisting of prefaces and sheet music, as well as critical reviews, sent to us by specialists, serving as templates for scientifically critical editions. The manuscript contents are subject to thorough examination. A large part of the work consists of comparing the delivered sheet music of a Händel work with the historic sources. We often spend months on finding, correcting and editing mistakes, in collaboration with these experts. Once that part of the process is complete, we start the correction phase, after which the publisher takes over the revised manuscript.

Researching Händel's works is especially complicated and time consuming, for his works were very popular and were played multiple times, in various different editions, authorized by Händel. In one case, there are twelve different editions of one work, which today are comprehensible solely because of the many handwritten supplements in Händel's performance scores, all of which need to be reconstructed, considered and weighted when creating a new edition, against the edition of the first performance.

Do you ever have to decide on a version, or do you use plenty of footnotes?

It is impossible to avoid footnotes. However if there's too many, a publisher will instead refer to the critical reviews with just one footnote...

Photo: Swen Reichhold / Universität Leipzig

You live in Leipzig. Do you also work here?

One day a week I work at the University Library in Leipzig, on a database for cataloging music sources (RISM). My job is to attribute and catalogue different source material, register beginnings of music, and so on. On the fifth day, I focus on my own, free research topics. This work may also take up parts of my weekend...

You specialize in the 18th century, which covers a «comprehensible» viola repertoire. What is it that fascinates you about the viola, and about the viola in the 18th century?

Naturally speaking, I love the sound of the viola. As a typical middle voice instrument, it is embedded in classical orchestration and only stands out when absent. During the 18th century, the viola was widely misunderstood, and people had just begun considering it as a solo instrument. In chamber music on the other hand, the viola has a prominent appearance. Violists had a notorious reputation at court orchestras back in time. They usually consisted of relegated violinists, who didn't play well enough. In my opinion, the roots of the viola's contempt lie in the 18th century. Even though, it is etymologically seen as the head of string instruments: The violin is the smaller form of the viola. Violione would be the bigger viola, and violoncello the «small biggie».

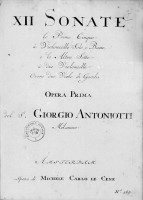

You discovered Giorgio Antoniotto. He wrote two solo sonatas for viola in the 1750s. What are these works' characteristics?

I found these works just by chance, in the international music sources database RISM. Washington's Library of Congress holds an autograph of a sonata in E-flat major, dated November 1753. According to current records, this might be the earliest sonata for viola and basso continuo, existing as an autograph. Another sonata in F major might also have been composed in the 1750s. However the information in the database was unclear. That's why I had the works digitalised, so I could edit them later. The sonata in E-flat major has been recorded by violist Pauline Sachse: https://www.music4viola.info/werk-info/2/Antoniotto

Between 2010 and 2012, you released all of Ernst Wilhelm Wolf's string quartets as a critical edition in four volumes, with the Brandenburg music publisher ortus. It looks like a lot of work...

It's been a lot of work indeed. I dedicated my master thesis to the twelve string quartets by Wolf. We had been working on this project for many years, because the source situation was highly complex in some cases. We examined countless autographs, transcripts and first editions in a meticulous manner, which enabled us to retrace the way from composition to print in great detail.

I frequently work with sources from the Berliner Sing-Akademie, which can be found as depositums in the national library in Berlin. That's where I discovered Wolf. These sources had been missing since WW2. The only relic was a handwritten catalogue. Almost the entire collection was rediscovered in 1999, and brought back to Berlin in 2002.

How significant do you think Wolf was as a composer?

Wolf is a typical representative of the era between Baroque and Classic, just as the sons of Bach. Speaking of quality, he was a composer who knew his craft, writing great music based on counterpoint. He combines stylistic elements from Baroque and more modern eras. His works have hardly been played up to date. Recordings remain rare. In collaboration with the Pleyel-Quartet Köln, the five quartets were recorded:

https://www.jpc.de/jpcng/cpo/detail/-/art/ernst-wilhelm-wolf-streichquartett

II seek the dialogue with artists, in order to mention certain works. The edition is a first step in this process.

Another composition which you've published was written by Carl Benda...

Carl Benda is the son of Franz Benda, who himself was a concertmaster at the Prussian court orchestra. His two sons Friedrich and Carl had also become violinists at the court orchestra, and both of them wrote viola concertos. At ortus I was in charge of the first print of the viola concerto in F. Carl Benda furthermore wrote two sonatas for violin and harpsichord, in F and in E-flat. They are preserved as clean copy autographs, both dated on 1785.

The story with composer Markus Heinrich Grauel and Johann Gottlieb Graun, older brother of Carl Heinrich Graun, is interesting. How did you conclude that the concerto for viola in E-flat major wasn't written by Grauel, but much more likely by Graun?

I collaborated with reputable researchers, who are experts on the history of the Grauns. Christoph Henzel created the work index of the brothers, not an easy task, considering that their works were hard to distinguish back in time already. Grauel was a cellist at the Prussian court orchestra. Little is known about him, however I determined that this work doesn't suit him stylistically, but would be a much closer fit with instrumental composer J.G. Graun.

How come these wrongful attributions happen at all?

This isn't a unique occurrence at all. There are countless examples of contemporaries who wrote wrong names at the end of transcripts, maybe because they weren't sure which composer had written which work.

chamber concert "Preussische

Hofkapellbratschisten"

How do you protect yourself from counterfeiters?

Education prepares us well. The master program «Erschliessung älterer Musik» at the Technische Universität Dresden teaches exactly these protective methods. Students learn about the ink mixtures of past times, paper types, typical writing habits, and so on. Particularly with watermarks, faking becomes difficult. One would need to use paper from that particular era.

It almost sounds like criminal investigation work...

That is true, and it requires plenty of patience. It becomes interesting when the work autograph is missing, but there's contradicting work attributions. That's when we try to collect stylistical characteristics with the help of sources, in order to be able to determine the composer.

You are a member of the German viola community. Will people find you at the next viola convention?

Yes, and I would like to attend these conventions. I am looking to hold presentations on specialized topics, and also advertise for the website music4viola.info. I would like to build a committee of people who contribute with inpus, and exchange their scientific research on the website.

Mr. Schmidt, we'd like to thank you for this insightful interview!

Footnotes

Phillip Schmidt will soon publish a critical edition of the solo sonata in C minor for viola and basso continuo by Franz Benda.

Mr. Schmidt has also supported the following CD recordings in an advisory role:

• https://www.jpc.de/jpcng/cpo/detail/-/art/friedrich-wilhelm-heinrich-benda

• https://www.highresaudio.com/pauline-sachse-andreas-hecker-viola-galante

• To the exciting inputs of Phillip Schmidt

• To the sheet music of Franz Benda

• To the sheet music of Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Benda

Niklaus Rüegg

This blog article is written by Niklaus Rüegg, graduate of the Zurich International Opera Studio, graduate of the Basel Opera Academy, twice winner of the Migros Gifted Scholarship, numerous engagements in opera, operetta, musicals and concerts in Switzerland and abroad.

Rüegg has also been working as a music journalist for ten years and is responsible for the association pages of the VMS (Verband Musikschulen Schweiz) in the Schweizer Musikzeitung.

As a young man, Niklaus Rüegg had played the violin and viola.

Available in our online shop |

und Orchester - F.W.H.Benda

Basso continuo [Erstdruck] -

Franz Benda

» To Noema by Roger Faedi

» To Garm by Roger Faedi

Don't miss any Violablogs |

» Subscribe to our Newsletter for free

| Could also be of interest to you |

» Exercise or talent?

» Rediecovered: Alexander Presuhn

» Natalia Wächter - The interview

|

|

Visit and like us on Facebook.

Visit and like us on Facebook.» Music4Viola on Facebook