The Perfect Fit of a Viola |

Arching, Wood and Elaboration - the Quality Criteria of a Good Viola

(Part 2)

Barbara Gschaider - Did you ever wonder how one recognizes a high-quality viola? If you’ve done your research, you may have come across one or another Stradivari re-incarnation: He or her cut, with their own hands, the last tree suitable for building high quality instruments. Or perhaps re-discovered a secret lacquer recipe? Secrets are still trending in the violin making industry. However, the reality looks very different, and after reading this article, you may think: A secret is by far not as mysterious as finding your sound in the real world!

Three Pillars for a Great Sound

While simple violas have easily recognizable attributes, a high-quality instrument is built on the harmonious interaction of wood, arching form, as well as the thickness of front and back (= weight). Keeping in mind, the interaction - a specific piece of wood or a specific arching form are useless on their own. A «good» instrument is always created if wood, arching and weight are hard enough to withstand the string pressure, yet still able to resonate freely, so that the sound can unfold. A violin maker may reach this goal in different ways. Let us first look at the individual elements: Pickup your viola - or violin, if necessary - and inspect it with the eyes of a violin maker:

Arching

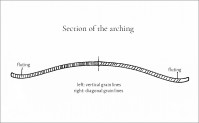

Let’s start with the structure of the arching, which is easily recognizable, even for an untrained eye: Looking from the edge, the arching falls like a hat’s brim, called fluting. After about one to three cm,  the arching ascends again towards the middle. Watch this ascension: Does it emerge spherically from the fluting, does it seem inflated and merge into a plateau? Or does the arching look similar to a roof with rounded peak? Also compare the arching form between upper bout and lower bout with the form of the middle bout: Is the ascension the same everywhere, or do you rather see the middle as a sphere, and the lower part as a roof? To get a feeling for the depth of the fluting, pour some water (in your mind!) on the viola front. How wide and deep would the moat be?

the arching ascends again towards the middle. Watch this ascension: Does it emerge spherically from the fluting, does it seem inflated and merge into a plateau? Or does the arching look similar to a roof with rounded peak? Also compare the arching form between upper bout and lower bout with the form of the middle bout: Is the ascension the same everywhere, or do you rather see the middle as a sphere, and the lower part as a roof? To get a feeling for the depth of the fluting, pour some water (in your mind!) on the viola front. How wide and deep would the moat be?

Again: Whether the arching form is «good» or «bad», can’t be determined yet, as it depends on the interaction.

However, simple quality can be found when looking at the craftsmanship: Unfortunately, the untrained eye will have a hard time finding these subtleties. Try it anyways: Does the arching of your viola extend evenly, or can you find a flat part? And does the fluting extend harmonically into the arching?

Archings that don’t flow smoothly, usually don’t sound well either. Because these subtleties also require a lot of craftsmanship and aesthetic perception, we as violin makers conclude: If these steps in the making were executed roughly, it can be assumed that the entire instrument was built with a lack of care.

On the other side, masterful crafting is only a first hint towards good sound quality - again, everything depends on the interaction. Our next element is wood:

Wood

The front wood is of great interest, particularly: the distance of the grain lines among each other. Most of them are about one mm apart. How about on your viola? Are the ring distances even, or do they narrow towards the middle and extend towards the edge?

Now look at the viola from the endpin: To the grain lines look vertical, or slightly diagonal? Unfortunately, a few important criteria can’t be seen on the finished instrument anymore, neither by the amateur, nor by the professional:

amateur, nor by the professional:

-

Grain alignment of the wood: When splitting a wooden wedge, you can clearly see the grain alignment: In some cases, you’ll find almost flat cleavages, in others the wood is spirally grown. The more evenly the grain alignment, the more stable the wood.

-

The specific weight of the wood.

With quality wood, just as with the arching, only inferior quality can be quickly and accurately identified: if the grain lines in the middle lie (the rules are different on the edge) further than two millimeters apart, the wood is undoubtedly too weak, and the instrument is probably of simple quality (although I have found exceptions). Well grown wood on the other side must be looked at in context with thearching, and especially the thickness of the front and the back:

The Thickness of Front and Back

The thickness of the front and the back of a finished instrument can only be determined with a special measuring device. For those who don’t own such a device, the total weight gives a hint on this thickness. Musicians often have a very developed sense for the total weight: Heavy instruments are often, but not always (!) thicker too. And: Heavy instruments are most often not well processed.

First Conclusion

As you may have realized, simple quality is easily recognizable by a violin maker. I can classify about 95% of all storage findings as of simple quality with this quick look - there’s a good reason for an instrument to be put in the storage. If the viola passes this first examination, it is then determined whether the all critical interaction works:

Effect on the Sound

As for the sound quality, I need to know how stable the wood, arching and thickness are, or how freely they let the viola vibrate.

A viola vibrates more

-

the wider and deeper the fluting

-

the lesser the stability of the front

-

the more diagonal the grain lines

-

the larger the distance between the grain lines

-

the more sagging the arching’s ascension

Stability depends on:

-

A narrow, flat fluting

-

a balloon-like arching ascension

-

narrow and vertical grain lines

-

a thick front

The thickness of the front and the back furthermore contributes to the sound:

-

Heavier weight leads to more damping.

You know this phenomenon from the string mute. If placing a mute on the viola bridge, all you really do is adding weight.

Anything supporting vibration sonically leads to a soft and easy response. Elements supporting stability enrich the sound with power and fullness. However, many effects cancel each other out, for example: If I  create a thinner viola front, the instrument vibrates more freely and the sound should become softer. However, because the instrument loses weight as well, the damping effect is lessened. Less damping makes the sound louder, and also sharper. Which effect remains depends on many factors, including the arching form. The exact point of removing wood is critical: The effect on stability is bigger between the f-holes, in the corners and along the fluting, but in the upper bout and lower bout, the weight is more significant. Sounds complicated? Yes, it is. Because the effects are very subtle, the sonic assessment of the instrument from its looks is largely a matter of experience. Inferior quality is again easily recognized: Instruments that aren’t balanced, meaning too stiff or flexible. A balanced viola on the other hand has good sound potential - but that doesn’t mean every performer will like it!

create a thinner viola front, the instrument vibrates more freely and the sound should become softer. However, because the instrument loses weight as well, the damping effect is lessened. Less damping makes the sound louder, and also sharper. Which effect remains depends on many factors, including the arching form. The exact point of removing wood is critical: The effect on stability is bigger between the f-holes, in the corners and along the fluting, but in the upper bout and lower bout, the weight is more significant. Sounds complicated? Yes, it is. Because the effects are very subtle, the sonic assessment of the instrument from its looks is largely a matter of experience. Inferior quality is again easily recognized: Instruments that aren’t balanced, meaning too stiff or flexible. A balanced viola on the other hand has good sound potential - but that doesn’t mean every performer will like it!

Regardless of personal taste, no violin maker is able to determine the sound of an unfamiliar instrument just by its looks. Too many details can’t be assessed retrospectively.

The case is a different one with instruments we build ourselves:

Sound Comparison Between a Maggini and an A.Guarneri Model

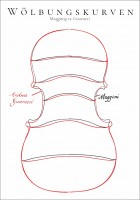

Another example including my two favorite violas by Maggini and Guarneri:

Looking at the arching of the Andrea Guarneri model, you’ll find: This arching is very balanced in itself. The fluting with its width and depth is quite flexible. The arching shows a roof in the upper bout and lower bout, and a balloon in the middle. With this model, a violin maker can’t go wrong. With stiff wood, the viola sounds more powerful, while flexible wood makes the sound softer. I like to  finish the front as evenly as possible, until it feels “just right”. I test the progress through pressing, bending and knocking on certain spots. When creating a A.Guarneri style model and as long as avoiding extremes, I always seem to receive a well balanced viola, with a sound that many violists seem to like.

finish the front as evenly as possible, until it feels “just right”. I test the progress through pressing, bending and knocking on certain spots. When creating a A.Guarneri style model and as long as avoiding extremes, I always seem to receive a well balanced viola, with a sound that many violists seem to like.

The Maggini is completely different. The arching is very full, the fluting very narrow. That means the entire arching is extremely stiff. If the grain lines in the wood are narrowly aligned and vertical up to the edge, the viola can barely move. A thinner working to balance wouldn’t really improve the sound, as with so much stiffness in the arching, the lower damping would draw too much attention: The viola would hence be very loud, probably even with a screaming sound quality. I only receive good results if building the Maggini with flexible wood. Stiff wood with vertical grain lines, which are at most one millimeter apart from each other, generally counts as «good» wood among violin makers, and is very expensive with timber merchants. For a Maggini replica however, this would be overkill. With so-called “inferior” wood, the viola sounds warmer and softer. Very important by the way: The fluting must be deep and thin enough, to increase the flexibility. You may wonder: Why would a violin maker not just build Andrea Guarneri replicas? My answer: Reconstructing an uncommon Maggini model with love and attention to detail leads to an uncommonly good sound too! The dark timbre is generally perceived as pleasant, yet the sound is strong enough to carry in the concert hall.

Final Note

Even though wood, arching, and strength of front and back form the viola sound, these elements should never be seen isolated. A large viola with the same arching, thickness and wood will sound different from a smaller instrument. Another crucial ingredient in the viola’s sound cocktail is the fitting up, speaking of bridge, sound post and strings, which I will talk about in the next blog article.

-

To read more: on https://www.atelier-gschaider.de/start-deutsch/Bücher you will find my book recommendations.

Here it goes to part 1: Body size and string length

This blog article was written by Barbara Gschaider. She is a violin maker and runs a workshop in Bonn together with her husband. The main focus of her work is the viola. She also works as an author on the subject of violin making.

www.atelier-gschaider.de

Photos: Barbara Gschaider

Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767)

12 Fantasias for viola solo

TWV 40:26-37 (1735)

Arranged and edited from the first edition for viola da gamba by

Viacheslav Dinerchtein

to the product card

» to the product

Building a viola in only 4 days

In November 2018 the International Viola Congress (IVC) took place in Rotterdam, Holland. During these four days four string instrument makers built a viola together. We were there and reported live.

» to the blog post

Georg Philipp Telemann was one of the most important composers of the Baroque period. He contributed innovative impulses to the development of music and significantly changed the musical world of the early 18th century.

» to the blog post

Hermann Ritter and his viola alta

Hermann Ritter, now generally quite forgotten, was actually one of the most respected and influential personalities in the history of the viola. Lionel Tertis is considered the first viola soloist. But that's not true...

» to the blog post

|

Viola news letter |

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our monthly viola news letter will keep you informed.

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our monthly viola news letter will keep you informed.» Subscribe to our viola letter for free

|

|

Visit and like us on Facebook.

Visit and like us on Facebook.» Music4Viola on Facebook